‼️

Prof Responsibility • Candor

PR#076

Legal Definition

In both California and under the ABA rules, a criminal defendant’s constitutional right to testify means that a lawyer must allow the defendant to testify, even if the lawyer reasonably believes the testimony will be false.

The lawyer must still:

(1) attempt to dissuade the defendant from testifying falsely, and if unsuccessful,

(2) request permission to withdraw.

However, unlike the ABA rules, which require the lawyer to disclose false testimony to the court as a last resort (even if it involves revealing confidential information), California rules prohibit such disclosure. Instead, if a California lawyer knows the testimony will be false, they may call the defendant as a witness and question them in the normal manner until the point of falsehood. From there, the lawyer must allow the defendant to testify in a narrative fashion but cannot use the false testimony in their closing argument.

Additionally, unlike the ABA rules, California does not permit a lawyer to reveal privileged or confidential information to correct false testimony.

The lawyer must still:

(1) attempt to dissuade the defendant from testifying falsely, and if unsuccessful,

(2) request permission to withdraw.

However, unlike the ABA rules, which require the lawyer to disclose false testimony to the court as a last resort (even if it involves revealing confidential information), California rules prohibit such disclosure. Instead, if a California lawyer knows the testimony will be false, they may call the defendant as a witness and question them in the normal manner until the point of falsehood. From there, the lawyer must allow the defendant to testify in a narrative fashion but cannot use the false testimony in their closing argument.

Additionally, unlike the ABA rules, California does not permit a lawyer to reveal privileged or confidential information to correct false testimony.

Plain English Explanation

In both California and other states, lawyers can't stop their clients from testifying, even if they think the client will lie. This comes from the Constitution, which gives defendants the right to tell their side of the story. But lawyers also have a duty to be honest with the court. So what's a lawyer to do?

First things first: the lawyer must try to talk the client out of lying. They might say, "Look, I know you want to protect yourself, but lying under oath is a crime. It could make things way worse for you." If that doesn't work, the lawyer's next move is to ask the judge for permission to quit the case. But judges often say no, especially if the trial is about to start.

Here's where things get really tricky. Under the ABA Rules, if all else fails, the lawyer has to tell the judge about the lie. It's like being forced to tattle on your best friend – uncomfortable, but sometimes necessary.

California, however, does things differently. California lawyers can't spill the beans on their clients. Instead, they use a clever workaround. They let the client testify but change how they ask questions. Instead of the usual back-and-forth, they simply say, "Tell the court what happened." This way, the lawyer isn't actively helping with the lie.

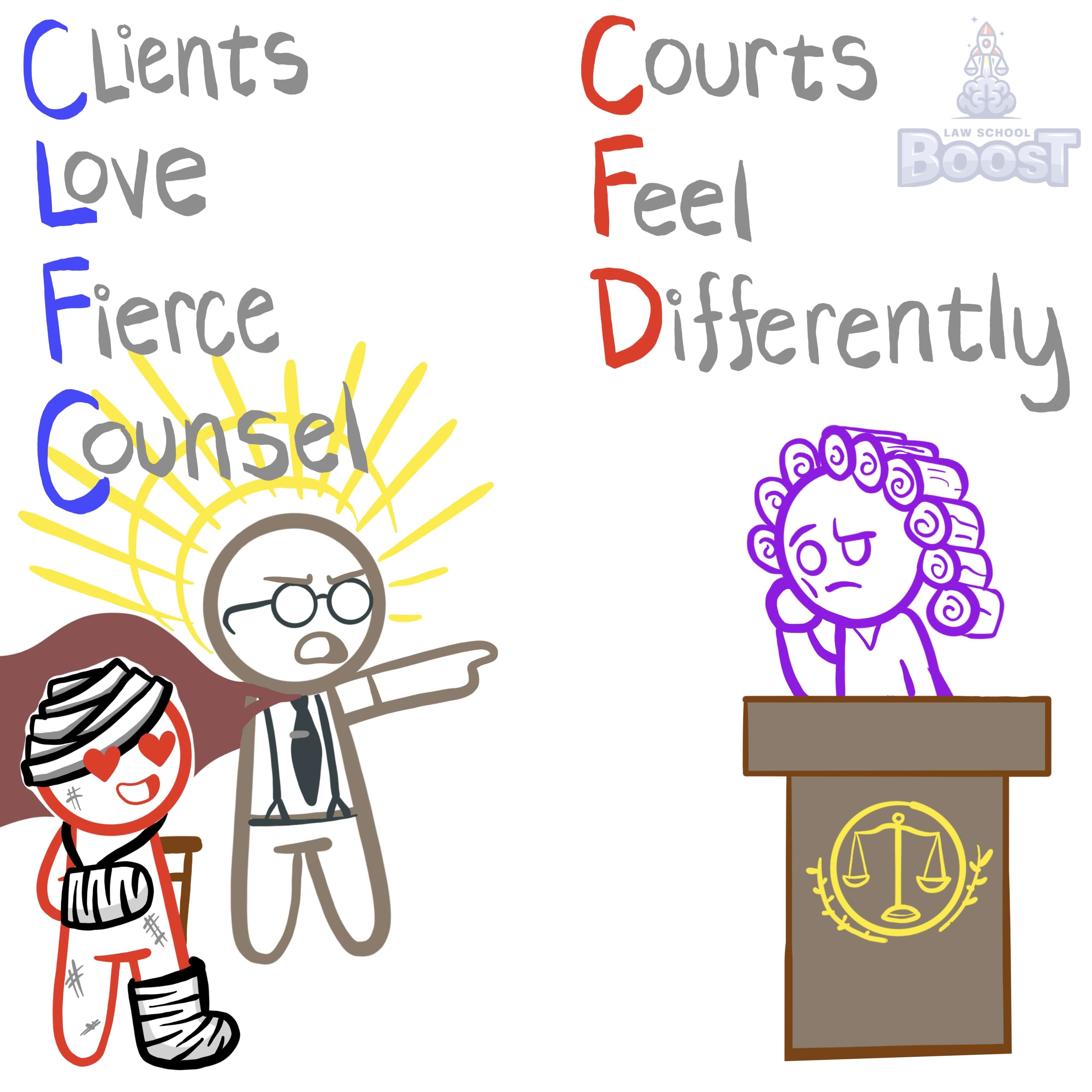

This difference shows how states struggle to balance competing goals. On one hand, we want trials to uncover the truth. On the other, we want people to trust their lawyers completely. California leans more towards protecting that trust, while other states prioritize honesty in court.

First things first: the lawyer must try to talk the client out of lying. They might say, "Look, I know you want to protect yourself, but lying under oath is a crime. It could make things way worse for you." If that doesn't work, the lawyer's next move is to ask the judge for permission to quit the case. But judges often say no, especially if the trial is about to start.

Here's where things get really tricky. Under the ABA Rules, if all else fails, the lawyer has to tell the judge about the lie. It's like being forced to tattle on your best friend – uncomfortable, but sometimes necessary.

California, however, does things differently. California lawyers can't spill the beans on their clients. Instead, they use a clever workaround. They let the client testify but change how they ask questions. Instead of the usual back-and-forth, they simply say, "Tell the court what happened." This way, the lawyer isn't actively helping with the lie.

This difference shows how states struggle to balance competing goals. On one hand, we want trials to uncover the truth. On the other, we want people to trust their lawyers completely. California leans more towards protecting that trust, while other states prioritize honesty in court.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob is representing Sam in a criminal trial for armed robbery. During trial preparation, Sam tells Bob that he plans to testify that he was at home watching TV at the time of the robbery. Bob knows this is false because Sam previously admitted to Bob that he committed the robbery. Bob tries to dissuade Sam from lying on the stand, but Sam insists on testifying. Result: Because it is a criminal trial, Bob cannot prevent Sam from testifying. Bob should question Sam normally about background information, then switch to narrative questioning when they reach the false alibi testimony. Bob cannot use the false alibi in his closing argument. Bob is prohibited from disclosing Sam's false testimony to the court.

Hypo 2: Same facts as Hypo 1, but Bob practices in a jurisdiction following the ABA Model Rules. Result: Bob should first try to dissuade Sam from testifying falsely. If that fails, Bob should seek to withdraw from the case. If withdrawal is not permitted or does not solve the problem, Bob must disclose Sam's false testimony to the court, even if it means revealing confidential client information.

Hypo 3: Bob is defending Sam against assault charges. Sam wants to testify that the victim attacked him first and he acted in self-defense. Bob has no reason to believe this is false, but he's not entirely sure it's true either. Result: In both California and ABA jurisdictions, Bob can allow Sam to testify. The duty to refrain from presenting false testimony only applies when the lawyer "knows" the testimony will be false. Mere suspicion or uncertainty is not enough to trigger this duty.

Hypo 4: Bob is representing Sam in a civil lawsuit. During his deposition, Sam lies about a material fact. Bob knows this testimony is false based on what Sam previously told him in confidence. Result: This scenario does not implicate the special rules for criminal defendants' testimony. In both California and ABA jurisdictions, Bob must take reasonable remedial measures, which may include disclosing the false testimony to the court if necessary. The constitutional right to testify, which complicates the analysis in criminal cases, does not apply in civil matters.

Hypo 2: Same facts as Hypo 1, but Bob practices in a jurisdiction following the ABA Model Rules. Result: Bob should first try to dissuade Sam from testifying falsely. If that fails, Bob should seek to withdraw from the case. If withdrawal is not permitted or does not solve the problem, Bob must disclose Sam's false testimony to the court, even if it means revealing confidential client information.

Hypo 3: Bob is defending Sam against assault charges. Sam wants to testify that the victim attacked him first and he acted in self-defense. Bob has no reason to believe this is false, but he's not entirely sure it's true either. Result: In both California and ABA jurisdictions, Bob can allow Sam to testify. The duty to refrain from presenting false testimony only applies when the lawyer "knows" the testimony will be false. Mere suspicion or uncertainty is not enough to trigger this duty.

Hypo 4: Bob is representing Sam in a civil lawsuit. During his deposition, Sam lies about a material fact. Bob knows this testimony is false based on what Sam previously told him in confidence. Result: This scenario does not implicate the special rules for criminal defendants' testimony. In both California and ABA jurisdictions, Bob must take reasonable remedial measures, which may include disclosing the false testimony to the court if necessary. The constitutional right to testify, which complicates the analysis in criminal cases, does not apply in civil matters.

Visual Aids

Related Concepts

According to the Duty Not to Contact Represented Parties, which individuals within an organization must an attorney obtain permission from the organization's lawyer before contacting directly?

Can lawyers compensate witnesses?

How must a lawyer balance their Duty of Candor with their criminal defendant client's right to testify if they believe they intend to lie?

In California, can an attorney disclose information to set the record straight if one of their witnesses intends to lie?

What are the 9 Affirmative Duties of a Public Prosecutor?

What is an ex parte proceeding, and how does it affect what a lawyer must disclose?

What is the Duty Not to Contact Represented Parties?

What is the Duty of Candor?

What is the Duty to Produce Evidence?

What must a lawyer do if they know that their witness intends to lie in their testimony?