‼️

Prof Responsibility • Government

PR#046

Legal Definition

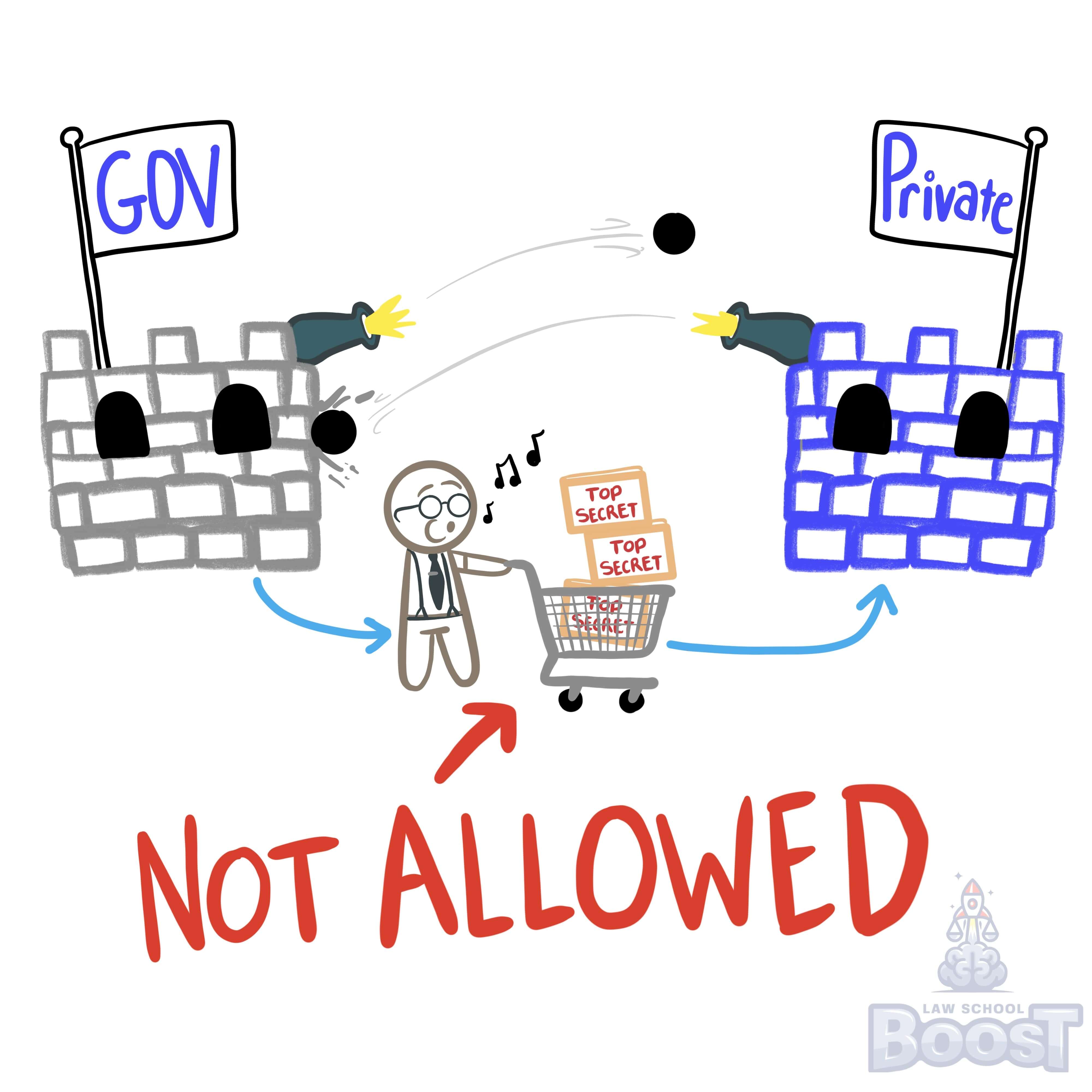

No, under Rule 1.11(a), a lawyer now in private practice may not represent a client in connection with a matter in which the lawyer participated personally and substantially as a government officer or employee, unless the appropriate government agency gives informed, written consent.

Plain English Explanation

When someone leaves a government job to become a private lawyer, they carry with them a wealth of inside knowledge. This rule is all about making sure that knowledge isn't misused in a way that's unfair to the government or undermines public trust.

Think of it like changing teams in a sports league. If you used to play for one team and knew all their secret plays, it wouldn't be fair to immediately join another team and use those secrets against your old teammates. Similarly, a former government lawyer can't switch sides and use their inside information against their old agency.

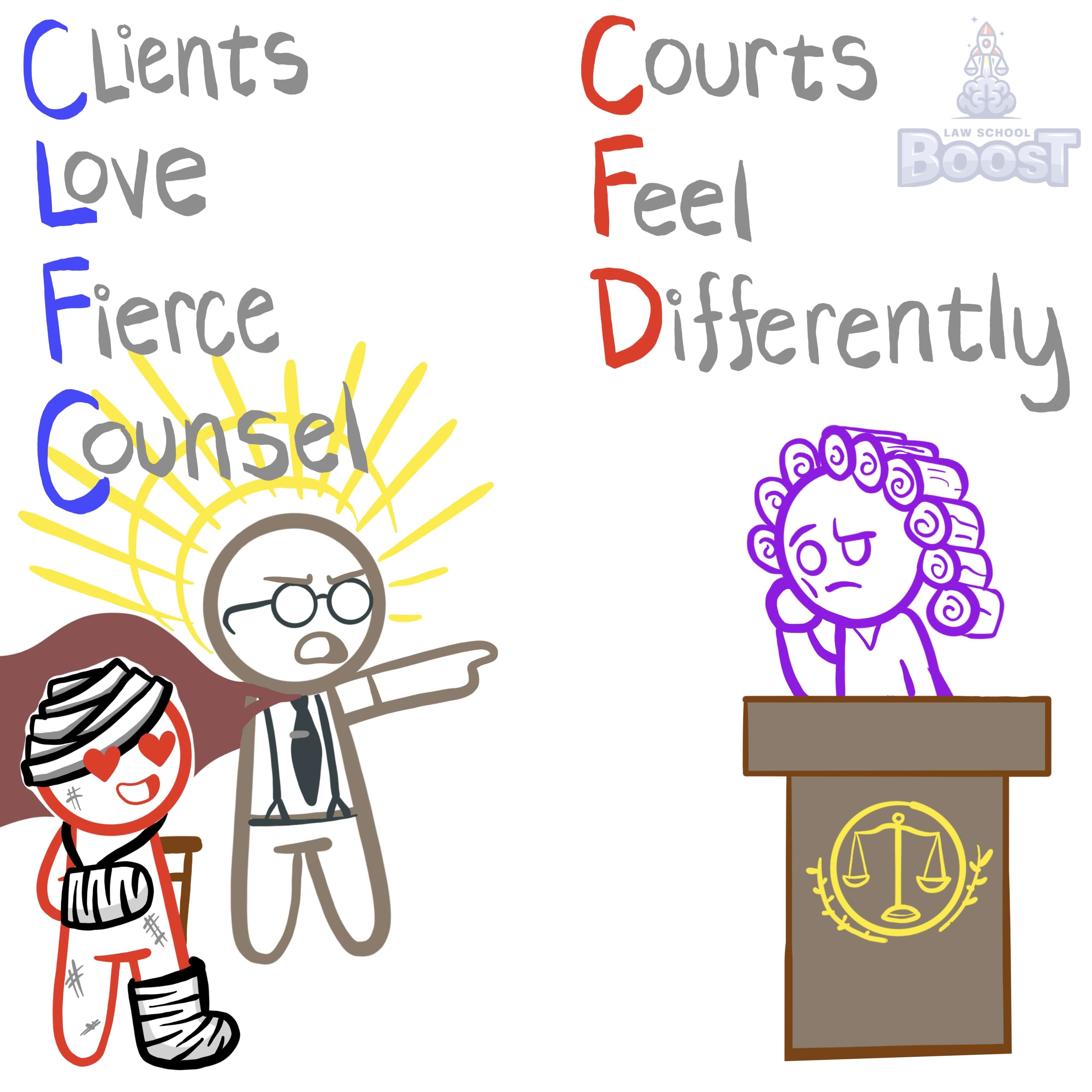

But what does it mean to have been "personally and substantially" involved? It's not just about being in the room or knowing a little bit about a case. It means you were a key player - making important decisions, handling critical information, or significantly shaping the government's approach.

The rule isn't absolute, though. There's a safety valve: if the government agency says it's okay, and puts that permission in writing, then the lawyer can take on the case. This written consent is important because it ensures the agency has really thought through the implications and decided that there's no real risk of unfair advantage.

Think of it like changing teams in a sports league. If you used to play for one team and knew all their secret plays, it wouldn't be fair to immediately join another team and use those secrets against your old teammates. Similarly, a former government lawyer can't switch sides and use their inside information against their old agency.

But what does it mean to have been "personally and substantially" involved? It's not just about being in the room or knowing a little bit about a case. It means you were a key player - making important decisions, handling critical information, or significantly shaping the government's approach.

The rule isn't absolute, though. There's a safety valve: if the government agency says it's okay, and puts that permission in writing, then the lawyer can take on the case. This written consent is important because it ensures the agency has really thought through the implications and decided that there's no real risk of unfair advantage.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob worked as a senior attorney for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for 10 years. During his tenure, he personally led an investigation into a major corporation's alleged violations of clean water regulations. Two years after leaving the EPA to start his own environmental law practice, the same corporation approaches Bob to represent them in the ongoing dispute with the EPA over those water violations. Result: Bob cannot represent the corporation in this matter without the EPA's informed, written consent. He was personally and substantially involved in the case while working for the government, having led the investigation himself. This is exactly the type of situation Rule 1.11(a) is designed to prevent, as Bob's inside knowledge could give his client an unfair advantage.

Hypo 2: Bob was a junior lawyer at the Department of Justice (DOJ) working in the antitrust division. While there, he occasionally sat in on meetings about a potential merger between two large tech companies, but he didn't contribute significantly to the case. After leaving the DOJ, he starts his own practice. One of the tech companies involved in that merger approaches him for representation in a new, unrelated patent dispute. Result: Bob can likely represent the tech company in the patent dispute. While he had some exposure to the merger case, his involvement doesn't seem to have been "personal and substantial." Moreover, the new case is unrelated to the merger he was exposed to at the DOJ. Rule 1.11(a) wouldn't prohibit this representation.

Hypo 3: Bob worked as a clerk for a federal judge for one year after law school. During this time, he assisted the judge on various cases but had no decision-making authority. After his clerkship, Bob starts his own practice. A client approaches him to represent them in an appeal of a case that was decided by the judge Bob clerked for, but it's a case that was heard after Bob's clerkship ended. Result: This situation likely doesn't fall under Rule 1.11(a). Bob's role as a clerk wouldn't typically be considered that of a "government officer or employee" in the context of this rule. Moreover, he had no involvement with this specific case, as it was decided after he left. Bob could likely represent this client without violating the rule, though he should be cautious about using any confidential information he may have learned during his clerkship.

Hypo 2: Bob was a junior lawyer at the Department of Justice (DOJ) working in the antitrust division. While there, he occasionally sat in on meetings about a potential merger between two large tech companies, but he didn't contribute significantly to the case. After leaving the DOJ, he starts his own practice. One of the tech companies involved in that merger approaches him for representation in a new, unrelated patent dispute. Result: Bob can likely represent the tech company in the patent dispute. While he had some exposure to the merger case, his involvement doesn't seem to have been "personal and substantial." Moreover, the new case is unrelated to the merger he was exposed to at the DOJ. Rule 1.11(a) wouldn't prohibit this representation.

Hypo 3: Bob worked as a clerk for a federal judge for one year after law school. During this time, he assisted the judge on various cases but had no decision-making authority. After his clerkship, Bob starts his own practice. A client approaches him to represent them in an appeal of a case that was decided by the judge Bob clerked for, but it's a case that was heard after Bob's clerkship ended. Result: This situation likely doesn't fall under Rule 1.11(a). Bob's role as a clerk wouldn't typically be considered that of a "government officer or employee" in the context of this rule. Moreover, he had no involvement with this specific case, as it was decided after he left. Bob could likely represent this client without violating the rule, though he should be cautious about using any confidential information he may have learned during his clerkship.

Visual Aids