‼️

Prof Responsibility • Withdrawal

PR#089

Legal Definition

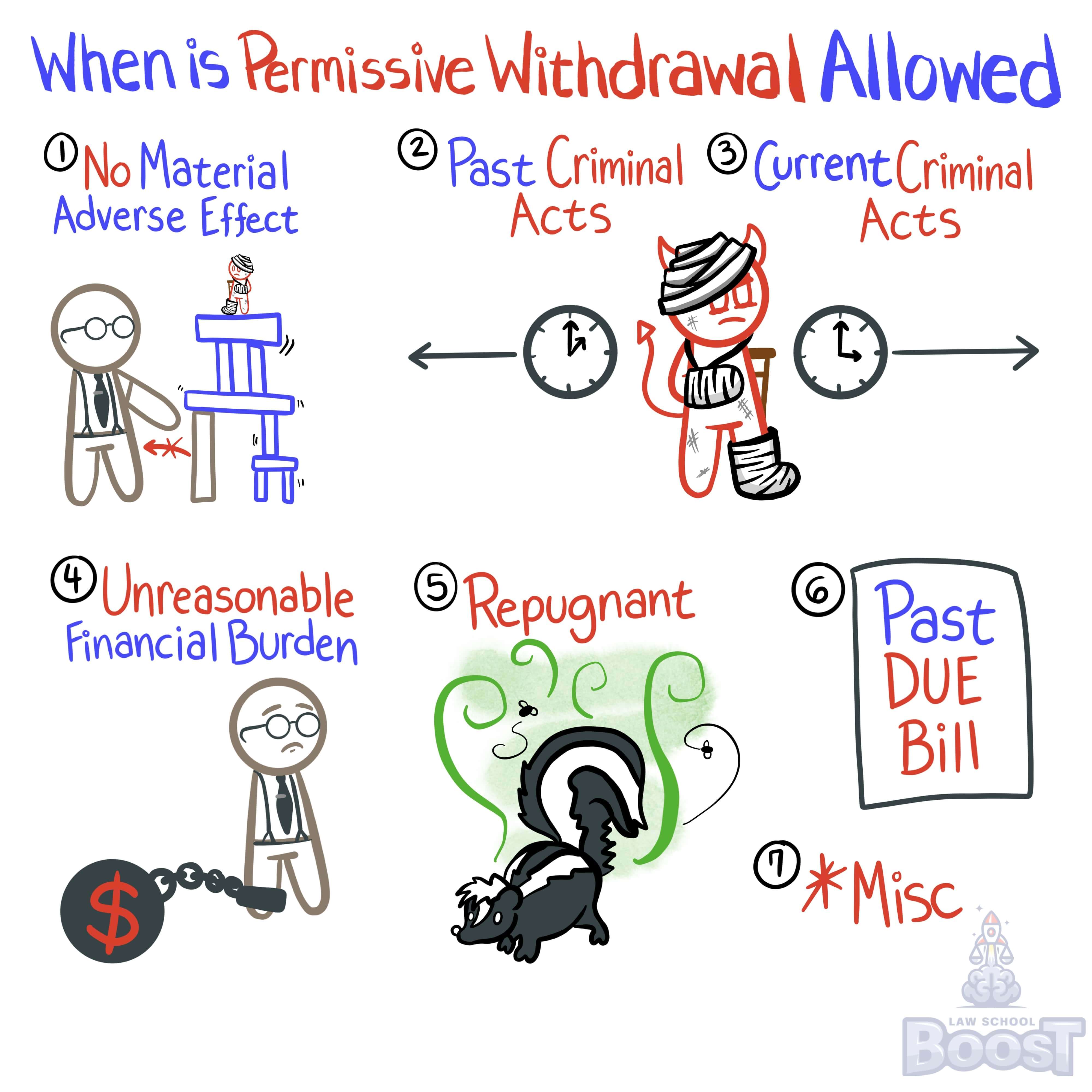

A lawyer may withdraw from representing a client if: (1) withdrawal can be accomplished without material adverse effect on the client's interests; (2) the client has used the lawyer's services to perpetrate a crime or fraud; (3) the client persists in a course of action involving the lawyer's services that the lawyer reasonably believes is criminal or fraudulent; (4) the representation will result in an unreasonable financial burden on the lawyer; (5) the client insists upon taking action the lawyer considers repugnant or with which the lawyer fundamentally disagrees; (6) the client fails substantially to fulfill an obligation to the lawyer regarding the lawyer's services and has been given a reasonable warning the lawyer will withdraw unless the obligation is fulfilled; and (7) where other good cause for withdrawal exists.

Plain English Explanation

Lawyers sometimes need to step away from a case, even when they're not required to. This is called permissive withdrawal, and it's like having an escape hatch if the attorney is put into an uncomfortable position and no longer wants to be tied to a client. There are seven situations where a lawyer is allowed to use the escape hatch:

(1) When both sides agree it’s time to move on. If a lawyer can step back without negatively impacting the client’s interests, they’re free to withdraw. It’s like ending a partnership when both parties realize they’re better off going separate ways.

(2) The client has used the lawyer's services for something shady. If a client uses their lawyer’s assistance to commit a crime or fraud, the lawyer can walk away. Think of it like a consultant discovering that their advice is being used to run a scam—they can, and should, leave.

(3) The client keeps pushing for illegal or fraudulent behavior. If a client insists on actions that the lawyer believes are criminal or fraudulent, the lawyer can back out. It’s like a financial advisor refusing to help when a client insists on using insider information.

(4) The case has turned into a financial sinkhole. When representation becomes an unexpected financial burden, the lawyer has grounds to withdraw. Imagine a local attorney taking on a case that unexpectedly demands costly international travel—they might need to step back to avoid going under.

(5) The client insists on something the lawyer finds repugnant. If a client demands actions that the lawyer fundamentally disagrees with, the lawyer can step aside. It’s like a chef choosing not to prepare a meal with ingredients they find ethically objectionable.

(6) The client isn’t holding up their end of the bargain. If a client fails to meet obligations, like paying fees after a warning, the lawyer can withdraw. Picture a contractor leaving a job after the homeowner repeatedly refuses to pay for completed work.

(7) Other good reasons to withdraw. This covers situations not explicitly listed in the other rules. Maybe there’s a total breakdown in communication, or an unforeseen conflict arises. It’s the legal version of “it’s complicated.”

In all these cases, the lawyer must still protect the client's interests when withdrawing. They need to give fair warning, allow time to find a new lawyer, and hand over any important documents. It's like quitting a job – you still need to give notice and help with the handover.

(1) When both sides agree it’s time to move on. If a lawyer can step back without negatively impacting the client’s interests, they’re free to withdraw. It’s like ending a partnership when both parties realize they’re better off going separate ways.

(2) The client has used the lawyer's services for something shady. If a client uses their lawyer’s assistance to commit a crime or fraud, the lawyer can walk away. Think of it like a consultant discovering that their advice is being used to run a scam—they can, and should, leave.

(3) The client keeps pushing for illegal or fraudulent behavior. If a client insists on actions that the lawyer believes are criminal or fraudulent, the lawyer can back out. It’s like a financial advisor refusing to help when a client insists on using insider information.

(4) The case has turned into a financial sinkhole. When representation becomes an unexpected financial burden, the lawyer has grounds to withdraw. Imagine a local attorney taking on a case that unexpectedly demands costly international travel—they might need to step back to avoid going under.

(5) The client insists on something the lawyer finds repugnant. If a client demands actions that the lawyer fundamentally disagrees with, the lawyer can step aside. It’s like a chef choosing not to prepare a meal with ingredients they find ethically objectionable.

(6) The client isn’t holding up their end of the bargain. If a client fails to meet obligations, like paying fees after a warning, the lawyer can withdraw. Picture a contractor leaving a job after the homeowner repeatedly refuses to pay for completed work.

(7) Other good reasons to withdraw. This covers situations not explicitly listed in the other rules. Maybe there’s a total breakdown in communication, or an unforeseen conflict arises. It’s the legal version of “it’s complicated.”

In all these cases, the lawyer must still protect the client's interests when withdrawing. They need to give fair warning, allow time to find a new lawyer, and hand over any important documents. It's like quitting a job – you still need to give notice and help with the handover.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob is representing Sam in a complex business litigation matter. As the case progresses, Sam becomes increasingly uncooperative - he fails to respond to Bob's requests for information, misses scheduled meetings, and ignores Bob's legal advice. Despite Bob's efforts to work with Sam, the lack of cooperation makes it extremely difficult for Bob to effectively prepare the case. Result: Bob likely has grounds for permissive withdrawal under the "unreasonably difficult" provision. Sam's uncooperative conduct has rendered the representation unreasonably difficult, impeding Bob's ability to competently handle the case. Before withdrawing, Bob should clearly communicate his concerns to Sam and give him an opportunity to cooperate. If Sam's conduct doesn't improve, Bob can ethically withdraw, following proper procedures.

Hypo 2: Bob is representing Sam in negotiating a business contract. Sam agreed to pay Bob's $300 hourly rate. After Bob has worked on the matter for two months, Sam stops paying Bob's invoices. Bob reminds Sam about the outstanding balance several times over the next month, but Sam fails to pay. Result: Bob likely has grounds for permissive withdrawal based on Sam's failure to fulfill a substantial financial obligation. Before withdrawing, Bob should give Sam clear written notice that he will withdraw if payment is not made by a specified date. If Sam still fails to pay after this warning, Bob can ethically withdraw, ensuring he protects Sam's interests in the process (e.g. by giving Sam time to find new counsel).

Hypo 2: Bob is representing Sam in negotiating a business contract. Sam agreed to pay Bob's $300 hourly rate. After Bob has worked on the matter for two months, Sam stops paying Bob's invoices. Bob reminds Sam about the outstanding balance several times over the next month, but Sam fails to pay. Result: Bob likely has grounds for permissive withdrawal based on Sam's failure to fulfill a substantial financial obligation. Before withdrawing, Bob should give Sam clear written notice that he will withdraw if payment is not made by a specified date. If Sam still fails to pay after this warning, Bob can ethically withdraw, ensuring he protects Sam's interests in the process (e.g. by giving Sam time to find new counsel).

Visual Aids

Related Concepts

In California, when does a lawyer have a mandatory Duty to Withdrawal or decline representation?

In California, when may an attorney choose to withdraw from representing a client (permissive withdraw)?

What is the procedure an attorney must follow to permissively withdrawal from representing a client?

When does a lawyer have a mandatory Duty to Withdrawal or decline representation?