‼️

Prof Responsibility • Duty to Public

PR#085

Legal Definition

In 2023, California adopted Rule 8.3, but it is much more limited compared to the ABA. It requires reporting only when a lawyer knows of "credible evidence" that another lawyer has committed a criminal act or engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or reckless or intentional misrepresentation that raises a substantial question about that lawyer's honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness as a lawyer. It does not apply to all violations of professional conduct, only to those involving serious criminal or fraudulent behavior. This rule does not require disclosure of privileged or confidential information.

Plain English Explanation

In 2023, California adopted Rule 8.3, which is similar to the ABA’s "Snitch Rule," but with significant differences in scope and application. The ABA Model Rule 8.3 requires lawyers to report any violations of the Rules of Professional Conduct that raise a substantial question about another lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness to practice law. This is a broad requirement that covers any serious ethical violation, not just criminal or fraudulent acts.

California’s Rule 8.3, however, is more limited. It only mandates reporting when a lawyer has "credible evidence" that another lawyer has committed a criminal act or has engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or reckless or intentional misrepresentation. Essentially, the California rule focuses on the most serious types of misconduct, such as criminal behavior or fraudulent acts that directly impact a lawyer’s honesty or trustworthiness.

Both rules emphasize that a lawyer’s duty to report does not extend to situations where the information is protected by confidentiality or privilege. This means that if reporting would require revealing a client’s confidential information, neither the ABA nor California’s Rule 8.3 would require the lawyer to report the misconduct.

California’s Rule 8.3, however, is more limited. It only mandates reporting when a lawyer has "credible evidence" that another lawyer has committed a criminal act or has engaged in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or reckless or intentional misrepresentation. Essentially, the California rule focuses on the most serious types of misconduct, such as criminal behavior or fraudulent acts that directly impact a lawyer’s honesty or trustworthiness.

Both rules emphasize that a lawyer’s duty to report does not extend to situations where the information is protected by confidentiality or privilege. This means that if reporting would require revealing a client’s confidential information, neither the ABA nor California’s Rule 8.3 would require the lawyer to report the misconduct.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob is representing Sam in a personal injury lawsuit. During discovery, Bob obtains concrete evidence that the opposing lawyer, Jane, has fabricated medical records to inflate her client's damages claim. Bob has copies of the original records and the falsified versions. Result: Bob has a duty to report Jane's conduct under California's rule. Fabricating evidence is a criminal act involving dishonesty that raises a substantial question about Jane's honesty and fitness as a lawyer. Bob has credible evidence of the misconduct, triggering the reporting obligation. Bob should report this to the appropriate disciplinary authority without disclosing any confidential client information.

Hypo 2: Bob is representing Sam in a contract dispute. Bob learns that the opposing lawyer, Tom, has been inflating his billable hours and overcharging his client. Bob only knows this because Sam overheard Tom bragging about it at a party. Result: Bob does not have a duty to report in this situation under California's rule. While overbilling clients could potentially involve dishonesty or fraud, Bob does not have credible evidence of the misconduct. His information is based on hearsay from his client rather than concrete proof. Without credible evidence, the duty to report is not triggered in California.

Hypo 3: Bob is at a legal conference where another lawyer, Mary, openly admits to routinely backdating documents for clients to help them evade tax liabilities. Mary provides specific examples of how she does this. Result: Bob has a duty to report Mary's conduct under California's rule. Backdating documents to evade taxes is both a criminal act and fraudulent conduct that raises substantial questions about Mary's honesty and fitness as a lawyer. Bob has credible evidence from Mary's own admission. The information was not obtained through a confidential client relationship, so Bob is free to report it.

Hypo 2: Bob is representing Sam in a contract dispute. Bob learns that the opposing lawyer, Tom, has been inflating his billable hours and overcharging his client. Bob only knows this because Sam overheard Tom bragging about it at a party. Result: Bob does not have a duty to report in this situation under California's rule. While overbilling clients could potentially involve dishonesty or fraud, Bob does not have credible evidence of the misconduct. His information is based on hearsay from his client rather than concrete proof. Without credible evidence, the duty to report is not triggered in California.

Hypo 3: Bob is at a legal conference where another lawyer, Mary, openly admits to routinely backdating documents for clients to help them evade tax liabilities. Mary provides specific examples of how she does this. Result: Bob has a duty to report Mary's conduct under California's rule. Backdating documents to evade taxes is both a criminal act and fraudulent conduct that raises substantial questions about Mary's honesty and fitness as a lawyer. Bob has credible evidence from Mary's own admission. The information was not obtained through a confidential client relationship, so Bob is free to report it.

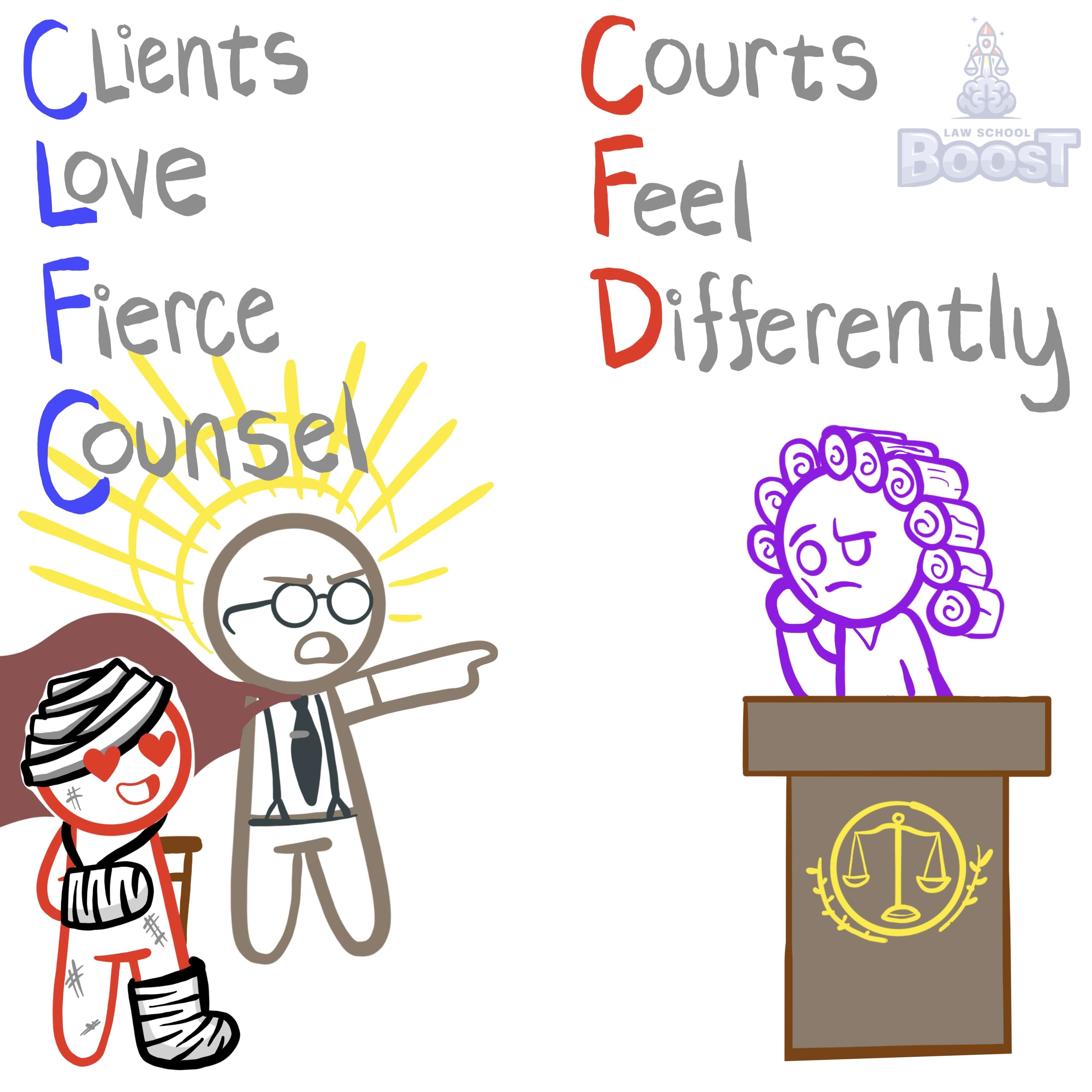

Visual Aids