‼️

Prof Responsibility • Financial Duties

PR#012

Legal Definition

In California, fees must not be "illegal or unconscionable." To determine if fees are unconscionable, California considers similar factors to the ABA, including: (1) the difficulty and novelty of the matter; (2) prevailing fees in the locale; and (3) how much time and business a lawyer must give up to take the case. Additional factors specific to California include: (4) the amount in proportion to the value of services; (5) the relative sophistication of the attorney and client; and (6) the client's informed consent to the fee.

Plain English Explanation

In California, fees must not be illegal or unconscionable, while under the ABA, fees must be reasonable. Both systems share similar factors to determine if a fee meets the required standard, but they also have important differences.

Common Factors:

Both California and the ABA consider the difficulty and novelty of the legal matter, the common fees in the area, and how much time and business the lawyer must give up to take the case. These factors ensure that fees reflect the complexity of the work and the lawyer’s opportunity costs.

Unique to California:

California specifically requires the fee to be proportional to the value of the services provided. This adds an extra layer of protection to ensure the fee is not excessively high compared to the service's worth. Additionally, California considers the relative sophistication of the attorney and the client, meaning the attorney's expertise and the client's understanding can affect what is considered fair. Finally, California emphasizes the importance of the client's informed consent to the fee arrangement, ensuring the client fully understands and agrees to the charges before work begins.

Unique to the ABA:

The ABA Rule includes factors such as whether the fee is fixed or contingent and any time limitations imposed by the client or circumstances. This means the ABA considers how the structure of the fee (e.g., contingency versus hourly) and any deadlines might impact its reasonableness. The ABA also looks at the amount involved and the results obtained, along with the experience, reputation, and ability of the lawyer performing the services, to determine if the fee is justified by the outcome and the lawyer’s qualifications.

Common Factors:

Both California and the ABA consider the difficulty and novelty of the legal matter, the common fees in the area, and how much time and business the lawyer must give up to take the case. These factors ensure that fees reflect the complexity of the work and the lawyer’s opportunity costs.

Unique to California:

California specifically requires the fee to be proportional to the value of the services provided. This adds an extra layer of protection to ensure the fee is not excessively high compared to the service's worth. Additionally, California considers the relative sophistication of the attorney and the client, meaning the attorney's expertise and the client's understanding can affect what is considered fair. Finally, California emphasizes the importance of the client's informed consent to the fee arrangement, ensuring the client fully understands and agrees to the charges before work begins.

Unique to the ABA:

The ABA Rule includes factors such as whether the fee is fixed or contingent and any time limitations imposed by the client or circumstances. This means the ABA considers how the structure of the fee (e.g., contingency versus hourly) and any deadlines might impact its reasonableness. The ABA also looks at the amount involved and the results obtained, along with the experience, reputation, and ability of the lawyer performing the services, to determine if the fee is justified by the outcome and the lawyer’s qualifications.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob, a newly licensed attorney in a small California town, takes on Sam's complex intellectual property case. Bob charges Sam $1,000 per hour, which is five times the rate of even the most experienced IP attorneys in their area. Sam, a small business owner with limited legal knowledge, agrees, believing Bob must be exceptionally skilled to charge such a high rate. Result: Bob's fee is likely unconscionable under California's rule. Factors (2) and (5) weigh heavily against Bob. The rate far exceeds local standards, and there's a significant disparity in sophistication between Bob and Sam. While factor (1) might justify higher fees due to the complexity of IP law, Bob's inexperience doesn't warrant such an extreme rate. Factor (6) is also problematic, as Sam's limited legal knowledge raises questions about whether his consent was truly informed.

Hypo 2: Sam, a tech startup founder, hires Bob, an experienced Silicon Valley lawyer, to handle a series of complex contract negotiations. Bob charges $800 per hour, which is within the standard range for top-tier corporate lawyers in the area. The negotiations unexpectedly become more intricate, requiring Bob to work around the clock and turn down other lucrative clients. Bob increases his rate to $1,000 per hour for the extra work. Result: Bob's fee increase is likely not unconscionable under California's rule. Factors (1), (2), and (3) support the increase. The case became more difficult and time-consuming than anticipated, requiring Bob to sacrifice other work. The new rate, while high, is still within the range for top Silicon Valley lawyers. Factors (4) and (5) also favor Bob - the amount charged is proportional to the valuable service provided, and Sam, as a tech entrepreneur, likely has sufficient sophistication to understand the fee structure. As long as Bob properly informed Sam of the increase (Factor 6), the fee should be acceptable.

Hypo 3: Sam, an elderly retiree with no legal experience, hires Bob to handle a simple will. Bob, knowing Sam has substantial savings, charges $10,000 for three hours of work. When Sam questions the fee, Bob quickly explains it's his "VIP rate" and has Sam sign an agreement. Result: This fee is likely unconscionable under California's rule. While Factor (2) might allow for higher rates in wealthy areas, the fee is grossly disproportionate to the service provided (factor 4). The simplicity of the task (Factor 1) and the vast difference in sophistication between Bob and Sam (Factor 5) further suggest the fee is unconscionable. Most importantly, Bob's hasty explanation and quick signing raise serious doubts about whether Sam gave informed consent (Factor 6). This fee would likely be deemed unconscionable.

Hypo 4: Sam, a mid-sized company, hires Bob's firm for ongoing legal work. Bob proposes a fee agreement where the company pays a monthly retainer of $10,000, which covers up to 30 hours of work. Any additional hours are billed at $400 per hour. The agreement also includes an annual 5% increase in rates. Sam's CFO, who has worked with several law firms before, reviews and signs the agreement. Result: This fee arrangement is likely not unconscionable under California's rule. The structure is common for ongoing corporate legal work, addressing Factors (2) and (4). The complexity of ongoing corporate legal needs satisfies Factor (1). Both parties seem sophisticated (Factor 5), and the detailed agreement and CFO's review suggest informed consent (Factor 6). While the annual increase might raise eyebrows, as long as it was clearly disclosed and agreed upon, it shouldn't render the fee unconscionable.

Hypo 5: Bob represents Sam in a personal injury case. They agree to a standard contingency fee of 33% if the case settles before trial, or 40% if it goes to trial. The agreement also states that Sam will be responsible for all costs associated with the case. However, Bob fails to include language explaining that Sam might still owe costs even if there is no recovery. Result: This fee agreement would likely be acceptable under ABA rules, which don't specifically require disclosure about costs in no-recovery scenarios. However, in California, this agreement is problematic. California requires contingency fee agreements to explicitly state whether the client will be liable for costs if there is no recovery. Bob's failure to include this information makes the fee agreement voidable at Sam's option, potentially limiting Bob to recovering only a reasonable fee for services actually rendered.

Hypo 2: Sam, a tech startup founder, hires Bob, an experienced Silicon Valley lawyer, to handle a series of complex contract negotiations. Bob charges $800 per hour, which is within the standard range for top-tier corporate lawyers in the area. The negotiations unexpectedly become more intricate, requiring Bob to work around the clock and turn down other lucrative clients. Bob increases his rate to $1,000 per hour for the extra work. Result: Bob's fee increase is likely not unconscionable under California's rule. Factors (1), (2), and (3) support the increase. The case became more difficult and time-consuming than anticipated, requiring Bob to sacrifice other work. The new rate, while high, is still within the range for top Silicon Valley lawyers. Factors (4) and (5) also favor Bob - the amount charged is proportional to the valuable service provided, and Sam, as a tech entrepreneur, likely has sufficient sophistication to understand the fee structure. As long as Bob properly informed Sam of the increase (Factor 6), the fee should be acceptable.

Hypo 3: Sam, an elderly retiree with no legal experience, hires Bob to handle a simple will. Bob, knowing Sam has substantial savings, charges $10,000 for three hours of work. When Sam questions the fee, Bob quickly explains it's his "VIP rate" and has Sam sign an agreement. Result: This fee is likely unconscionable under California's rule. While Factor (2) might allow for higher rates in wealthy areas, the fee is grossly disproportionate to the service provided (factor 4). The simplicity of the task (Factor 1) and the vast difference in sophistication between Bob and Sam (Factor 5) further suggest the fee is unconscionable. Most importantly, Bob's hasty explanation and quick signing raise serious doubts about whether Sam gave informed consent (Factor 6). This fee would likely be deemed unconscionable.

Hypo 4: Sam, a mid-sized company, hires Bob's firm for ongoing legal work. Bob proposes a fee agreement where the company pays a monthly retainer of $10,000, which covers up to 30 hours of work. Any additional hours are billed at $400 per hour. The agreement also includes an annual 5% increase in rates. Sam's CFO, who has worked with several law firms before, reviews and signs the agreement. Result: This fee arrangement is likely not unconscionable under California's rule. The structure is common for ongoing corporate legal work, addressing Factors (2) and (4). The complexity of ongoing corporate legal needs satisfies Factor (1). Both parties seem sophisticated (Factor 5), and the detailed agreement and CFO's review suggest informed consent (Factor 6). While the annual increase might raise eyebrows, as long as it was clearly disclosed and agreed upon, it shouldn't render the fee unconscionable.

Hypo 5: Bob represents Sam in a personal injury case. They agree to a standard contingency fee of 33% if the case settles before trial, or 40% if it goes to trial. The agreement also states that Sam will be responsible for all costs associated with the case. However, Bob fails to include language explaining that Sam might still owe costs even if there is no recovery. Result: This fee agreement would likely be acceptable under ABA rules, which don't specifically require disclosure about costs in no-recovery scenarios. However, in California, this agreement is problematic. California requires contingency fee agreements to explicitly state whether the client will be liable for costs if there is no recovery. Bob's failure to include this information makes the fee agreement voidable at Sam's option, potentially limiting Bob to recovering only a reasonable fee for services actually rendered.

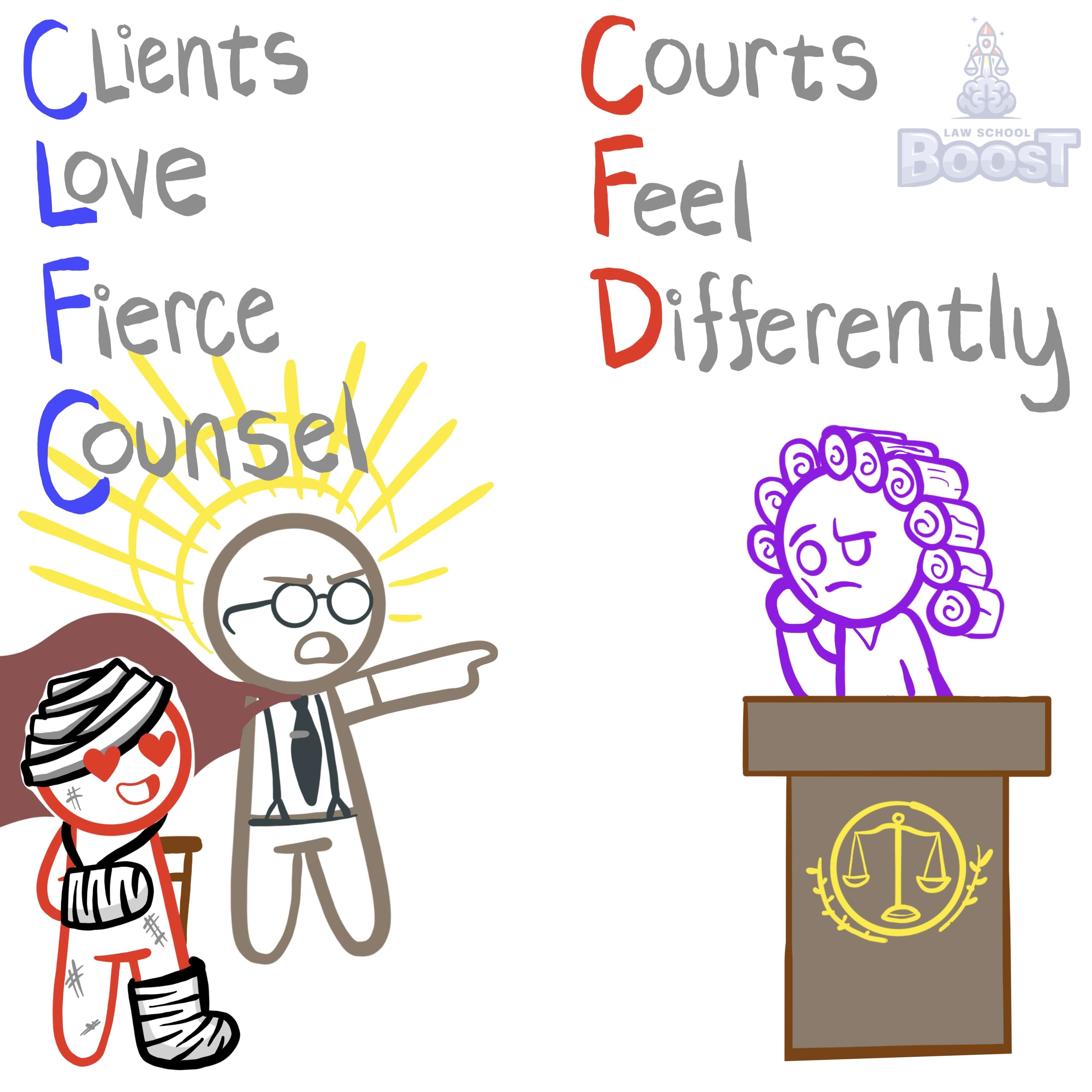

Visual Aids

Related Concepts

How and when must a lawyer determine fee arrangements with a new client?

How does California rule on fee splitting differ from the ABA?

How may a contingent fee be calculated?

In California, how and when must a lawyer determine fee arrangements with a new client?

Under the ABA, which types of cases are prohibited from contingent fee arrangements?

What constitutes "reasonable fees"?

What is a contingency fee?

What is required to fee split with another lawyer not in their firm?

What must a contingent fee offer warn the client of, and how?