🫶

Prof Responsibility • Loyalty

PR#020

Legal Definition

The distinction between an actual conflict and a potential conflict of interest is addressed in Rule 1.7:

Actual Conflict: According to Rule 1.7(a), an actual conflict exists when the representation of one client will be directly adverse to another client. This type of conflict is present and real, affecting the lawyer's ability to represent a client without being compromised by obligations to another client, a former client, or a third party.

Potential Conflict: Rule 1.7(a)(2) addresses potential conflicts, stating that a conflict exists if there is a significant risk that the lawyer's representation of one or more clients will be materially limited by the lawyer’s responsibilities to another client, a former client, a third person, or by a personal interest of the lawyer. This is more of a risk-based assessment, where the conflict could arise under certain circumstances but hasn't materialized yet .

Actual Conflict: According to Rule 1.7(a), an actual conflict exists when the representation of one client will be directly adverse to another client. This type of conflict is present and real, affecting the lawyer's ability to represent a client without being compromised by obligations to another client, a former client, or a third party.

Potential Conflict: Rule 1.7(a)(2) addresses potential conflicts, stating that a conflict exists if there is a significant risk that the lawyer's representation of one or more clients will be materially limited by the lawyer’s responsibilities to another client, a former client, a third person, or by a personal interest of the lawyer. This is more of a risk-based assessment, where the conflict could arise under certain circumstances but hasn't materialized yet .

Plain English Explanation

Think of an actual conflict as a "right now" problem. It's happening in the present, clear as day. The classic example is when a lawyer is asked to represent two clients who are directly opposing each other in a case. For instance, if a lawyer tried to represent both the plaintiff and the defendant in a lawsuit, that would be an actual conflict. It's obvious that the lawyer can't fully advocate for both sides simultaneously. This type of conflict is immediate and tangible - you can point to it and say, "There's the problem."

A potential conflict, on the other hand, is more of a "what if" scenario. It's not causing problems right now, but there's a real risk it could in the future. It's like dark clouds on the horizon - the storm hasn't hit yet, but there's a significant chance it will. For example, let's say a lawyer is representing a client in a business deal, and the lawyer's spouse owns stock in the company on the other side of the deal. Right now, this might not be affecting the lawyer's judgment, but there's a risk it could if the stakes get high enough. The key here is that there's a "significant risk" - not just any hypothetical scenario, but a genuine possibility that the lawyer's representation could be compromised.

Why does this distinction matter? Because it affects how lawyers need to handle these situations. Actual conflicts often require immediate action - the lawyer usually needs to decline representation or withdraw from the case. With potential conflicts, there might be more room for management. The lawyer might be able to continue representation if they disclose the potential conflict to the client and get their informed consent.

It's also worth noting that potential conflicts can turn into actual conflicts as circumstances change. That's why lawyers need to be vigilant, constantly assessing their cases for developing conflicts.

In both cases, the underlying principle is the same: safeguarding the lawyer's ability to provide loyal, uncompromised representation to their client. Whether it's an actual conflict staring them in the face or a potential conflict looming on the horizon, lawyers have a duty to identify, disclose, and address these issues to maintain their loyalty to their clients.

A potential conflict, on the other hand, is more of a "what if" scenario. It's not causing problems right now, but there's a real risk it could in the future. It's like dark clouds on the horizon - the storm hasn't hit yet, but there's a significant chance it will. For example, let's say a lawyer is representing a client in a business deal, and the lawyer's spouse owns stock in the company on the other side of the deal. Right now, this might not be affecting the lawyer's judgment, but there's a risk it could if the stakes get high enough. The key here is that there's a "significant risk" - not just any hypothetical scenario, but a genuine possibility that the lawyer's representation could be compromised.

Why does this distinction matter? Because it affects how lawyers need to handle these situations. Actual conflicts often require immediate action - the lawyer usually needs to decline representation or withdraw from the case. With potential conflicts, there might be more room for management. The lawyer might be able to continue representation if they disclose the potential conflict to the client and get their informed consent.

It's also worth noting that potential conflicts can turn into actual conflicts as circumstances change. That's why lawyers need to be vigilant, constantly assessing their cases for developing conflicts.

In both cases, the underlying principle is the same: safeguarding the lawyer's ability to provide loyal, uncompromised representation to their client. Whether it's an actual conflict staring them in the face or a potential conflict looming on the horizon, lawyers have a duty to identify, disclose, and address these issues to maintain their loyalty to their clients.

Hypothetical

Hypo 1: Bob, a lawyer, is asked to represent Sam in a lawsuit against BigCorp. Bob is currently representing BigCorp in an unrelated tax matter. Result: This is an actual conflict of interest under Rule 1.7(a). Bob's representation of Sam would be directly adverse to his current client, BigCorp. Even though the matters are unrelated, Bob cannot represent clients on opposite sides of a lawsuit without their informed consent. Bob must decline to represent Sam unless both Sam and BigCorp give informed consent and Bob reasonably believes he can provide competent representation to both clients.

Hypo 2: Bob is asked to represent Sam in a personal injury case. The defendant is a small local business. Bob remembers that he once bought a gift card from this business but has no other connection to it. Result: This scenario likely doesn't rise to the level of either an actual or potential conflict of interest. Bob's minor consumer interaction with the business doesn't create direct adversity, nor does it pose a significant risk of materially limiting his representation of Sam. Unless there are additional facts that would create a substantial risk of limiting Bob's representation, this minimal connection wouldn't typically require disclosure or consent under Rule 1.7.

Hypo 3: Bob is representing Sam in a contract dispute. Midway through the case, Bob learns that the key witness for the other side is his second cousin, whom he sees at family gatherings once a year. Result: This situation presents a potential conflict of interest under Rule 1.7(a)(2). While Bob isn't directly adverse to his cousin, there's a significant risk that his family relationship could materially limit his representation of Sam, particularly when it comes to cross-examining or challenging his cousin's testimony. Bob needs to disclose this relationship to Sam and assess whether he can continue to represent Sam competently and diligently despite this connection. If Bob believes he can proceed effectively and Sam gives informed consent after full disclosure, Bob may be able to continue the representation.

Hypo 2: Bob is asked to represent Sam in a personal injury case. The defendant is a small local business. Bob remembers that he once bought a gift card from this business but has no other connection to it. Result: This scenario likely doesn't rise to the level of either an actual or potential conflict of interest. Bob's minor consumer interaction with the business doesn't create direct adversity, nor does it pose a significant risk of materially limiting his representation of Sam. Unless there are additional facts that would create a substantial risk of limiting Bob's representation, this minimal connection wouldn't typically require disclosure or consent under Rule 1.7.

Hypo 3: Bob is representing Sam in a contract dispute. Midway through the case, Bob learns that the key witness for the other side is his second cousin, whom he sees at family gatherings once a year. Result: This situation presents a potential conflict of interest under Rule 1.7(a)(2). While Bob isn't directly adverse to his cousin, there's a significant risk that his family relationship could materially limit his representation of Sam, particularly when it comes to cross-examining or challenging his cousin's testimony. Bob needs to disclose this relationship to Sam and assess whether he can continue to represent Sam competently and diligently despite this connection. If Bob believes he can proceed effectively and Sam gives informed consent after full disclosure, Bob may be able to continue the representation.

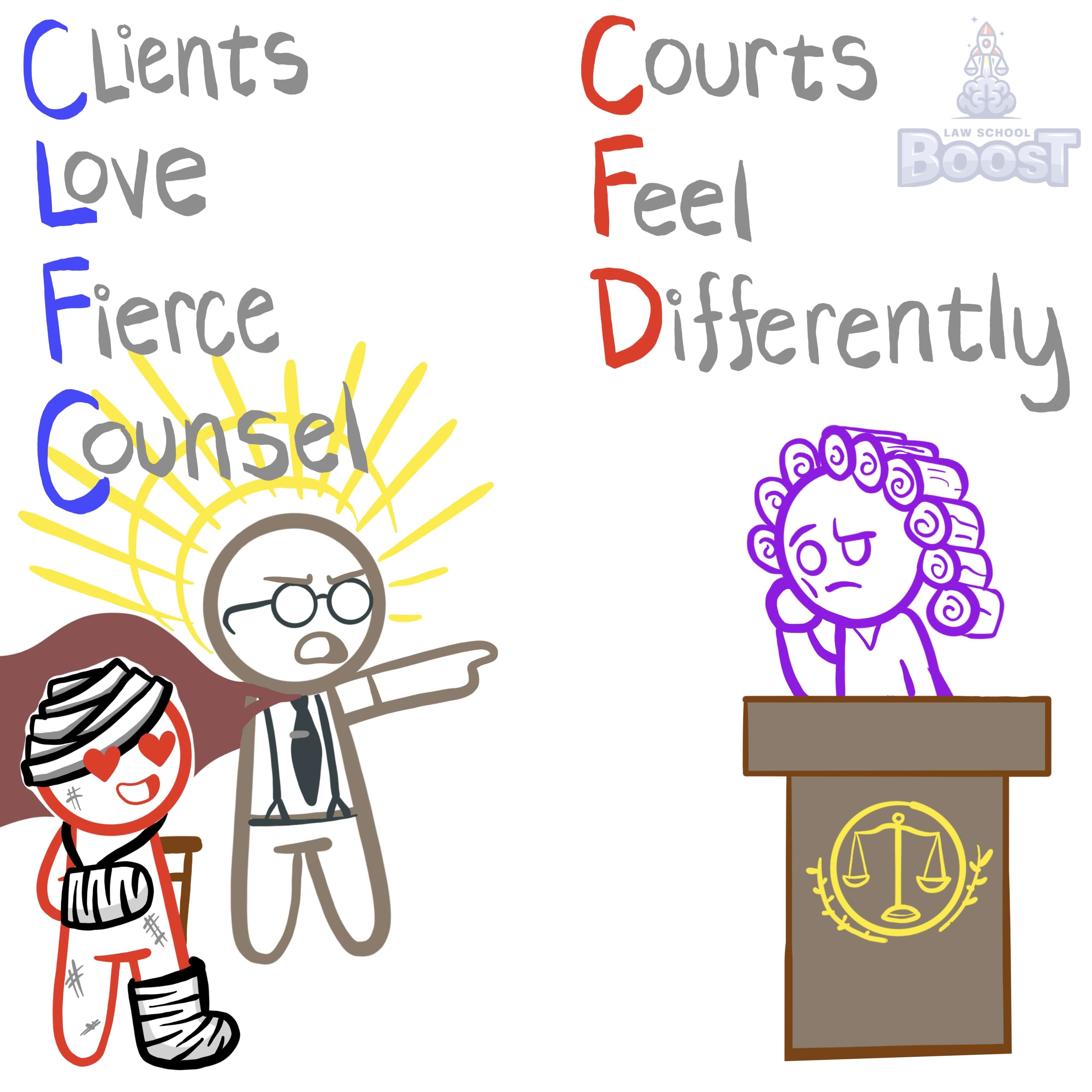

Visual Aids

Related Concepts

Does representing clients with inconsistent positions violate the lawyer's Duty of Loyalty?

In California, what are the restrictions related to lawyers acquiring the media rights of their clients?

What are some common issues that occur when a lawyer represents multiple clients in the same matter?

What are the restrictions related to lawyers receiving gifts from their clients?

When may a lawyer appear as a witness in a matter where they represent a party?